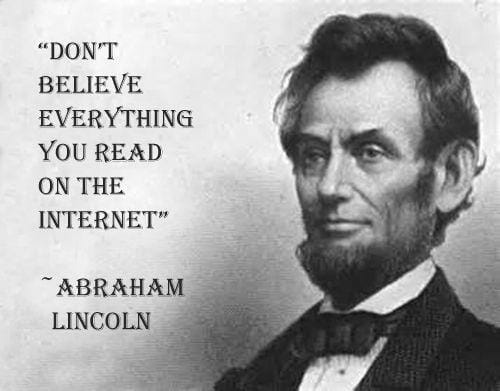

Over the past decade, it became more and more prevalent – it started with innocent motivational internet quotes, wrongly attributed to the wrong people. It sits well with our “common sense” – we have very little to doubt it It’s not completely ridiculous, so we accept it as “truth”. We believe what we see, accepting arbitrary quotes and stories as true (and quoting those to others, with complete certainty, and trusting of the source!). This is annoying but generally harmless… or is it?

For most people, this meme would be funny. However, most kids, especially outside of the USA, don’t have any idea who Abe was, so this meme looks highly credible to them – it’s a black and white picture of an ancient dude, with an older-style font. Why doubt it? That’s exactly how the manipulation of people’s minds begin. You take the ignorant, feed them wrong information, with the credibility of a meme. Do you think most people see through this, and know what’s right and wrong? Think again…

Here are some quotes to illustrate. You can read the rest on Mentalfloss.com and on Mashable.

“The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

The actual quote—“A journey of 400 miles begins beneath one’s feet”—was Lao Tzu, not Confucius.

“You want the truth? You can’t handle the truth.”

In A Few Good Men, Jack Nicholson’s character never utters the first part of the quote that’s so often attributed to him.

These are harmless examples. Misquoting a cult movie or an old Chinese philosopher, may annoy some people, but no real harm is done.

There are a few websites that are dedicated to correct wrong information, misguided information and to fight

Snopes

/snoʊps/ NOUN and sometimes VERB

We are the internet’s go-to source for discerning what is true and what is total nonsense.

Given the vast amount of information the internet has provided us with, most of us just take that information as

We perceive only a tiny portion of our environment, yet perception seems so very full. This illusion of fullness invites us to make wild cognitive leaps in blissful ignorance, and we repeatedly oblige.1

Daniel Kahneman explains it in his insightful book, Thinking Fast and Slow.

Kahneman starts his book by pointing out that human animals (his description, not mine!) have two often-conflicting systems for making decisions. System 1 is quick, dirty and automatic. System 2 must be engaged consciously, and with some effort.

WYSIATI is a function of “System 1,” and it encourages us to jump to conclusions based on that which is in front of us.

Jumping to conclusions on the basis of limited evidence is so important to an understanding of intuitive thinking, and comes up so often in this book, that I will use a cumbersome abbreviation for it: WYSIATI, which stands for what you see is all there is. System 1 is radically insensitive to both the quality and the quantity of the information that gives rise to impressions and intuitions.

Now take this insight about our human mind, and think about the way we consume information fed to us by others. Those “others” might be as gullible as we are, and unwittingly sharing false information. Or they could be less innocent than that. Those “others” could have an agenda. That agenda can be very, very dangerous…

Information Warfare

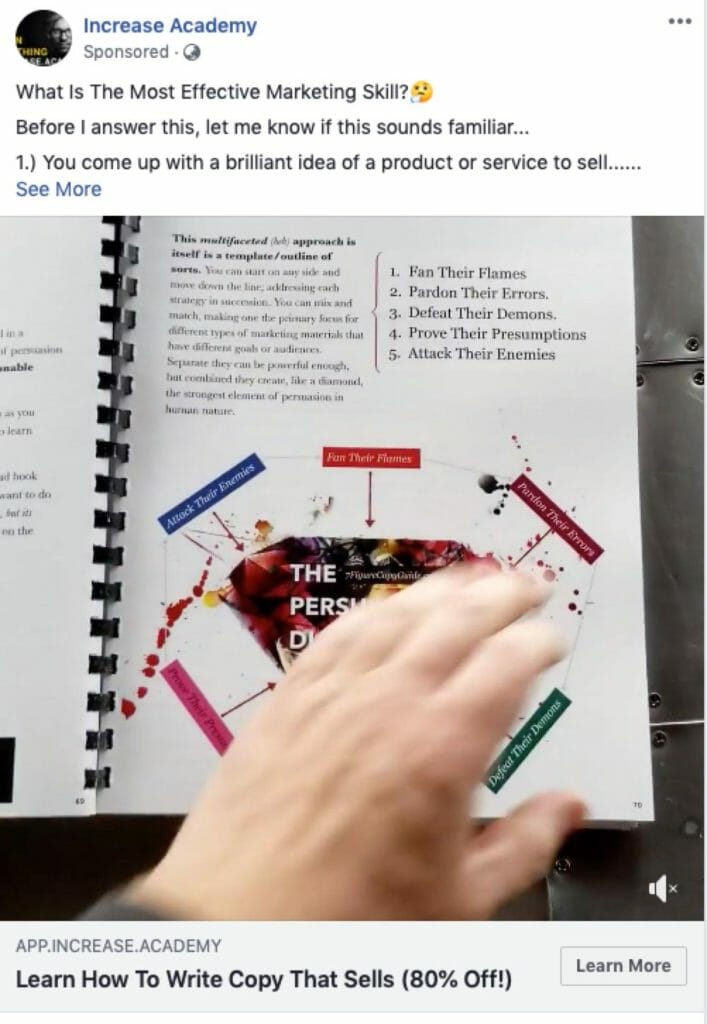

In a separate article, I wrote about the use of Psychographics in advertising and propaganda. Cambridge Analytica and similar companies today use targeted messaging to people who are most likely to be receptive to them. The FUD – Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt are all being used to propagate information specifically designed to shift people’s beliefs and behaviour in an orchestrated manner. Facebook is a great platform, allowing people to spread whichever message they wish – using sponsored posts (paid advertising), or emotionally charged memes. Meme, by definition, is a viral piece of information – information which spreads like a virus. Using the FUD elements, skilled people can (and do) create content to spread all over the internet, exploiting people’s most basic emotions…

That’s where we move more harmless misquotes, to warfare. The line is so thin, it’s frightening!

Marketing people do this in advertising every single day, to influence people to buy our products. We use fear and uncertainty to sell insurance, investments & sometime even real estate. We use other emotions to sell other goods and services.

Most people believe the ads they see, and buy the products relevant to them. Social networks are great at providing the platform, allowing advertisers to target individuals (i.e. you and me), and “serve” them with adverts which they are likely to buy, or at least be interested in them.

For example, as a marketer, and an avid motorcycle rider, I’ve collected these ads from my Facebook feed today:

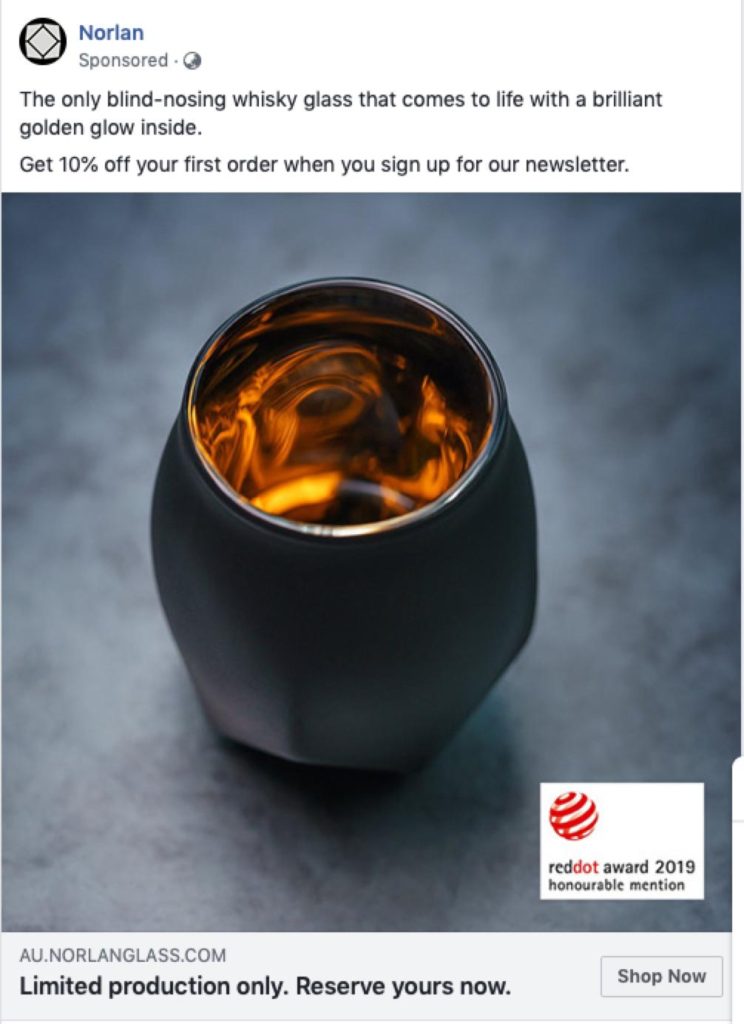

Oh, and I love my scotch too…

Yes, there were many more, some more relevant than the others. However – those are very

Facebook isn’t the only one learning about what we like or are interested in. There have been a long time rumour that Google actually reading our mail. Not only on Gmail (which is free for a reason), but also our other mail accounts. It’s not just Google, but other applications (just like Facebook), which we allow (knowingly or not) access to our accounts.

This isn’t about our privacy. I accepted that privacy is almost impossible to

If we know that we take memes as truths, and we believe ads from commercial entities, even though we KNOW they are manipulating us to buy their products, I’d like to bring up another possibility. Actually – this is already happening…

In The Great Hack, a Netflix production, it was made public that Cambridge Analytica had developed an app, designed to gather as much information as possible on people (not only US voters – it was done around the world). The app then produced enough data, to create a full OCEAN psychological profile of people. Political parties then used that data to create campaigns designed to sway voters away from their preferred candidates, by spreading rumours, lies and fake news about them. Since those lies “looked” legit (young way of saying – Legitimate), they had the anticipated effect – people liked them, shared them and voted accordingly.

Cambridge Analytica “practiced” around the world, in places like Trinidad & Tobago, Nigeria

Yes, information now can be weaponised. CB Insights, a Data & Research firm in New York have published a full report dealing with trends and activities in the digital information warfare space. It sounds as scary as it is:

Three key tactics, buoyed by supporting technologies, will play key roles in the future of war, as delineated in part by Aviv Ovadya, chief technology officer for the University of Michigan’s Centre for Social Media Responsibility:

- Diplomacy & reputational manipulation: the use of advanced digital deception technologies to incite unfounded diplomatic or military reactions in an adversary; or falsely impersonate and de-legitimize an adversary’s leaders and influencers.

- Automated laser phishing: the hyper-targeted use of malicious AI to mimic trustworthy entities that compel targets to act in ways they otherwise would not, including the release of secrets.

- Computational propaganda: the exploitation of social media, human psychology, rumour, gossip, and algorithms to manipulate public opinion.2 sobre esto

What can we do about it?

As individuals – not a lot. Warfare is a game played by governments. But we can be a little less gullible. We don’t have to believe everything we see on Facebook. Or any viral video someone sends us on WhatsApp group. It can be fake, or misleading, or even just a half-truth. Let’s pick up our game, and start screening the information we consume. Validate it. Use cross-referencing tactics, to get to the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

How do we do this?

- identify when you’re being played. If something you see is shocking, revealing, outrageous, appalling, makes you really sad or angry – stop! Check if it’s really true. See if you can find a reputable source of information, or even just ask other people – “is this likely to be true?” If it is –

check if it is… - Before sharing or commenting, stop! Make sure what you’re sharing is actually true. It may start with a Qantas free ticket promotion, or a petition against Facebook. Please check it first.

- Tell your friends, who are sharing these fake or untrue posts. Ask them (privately, if possible) if they’ve been hacked.

Otherwise there’s no way they would post something like that, right? RIGHT???

1Source – DangerousIntersecting.org

2Source – Memes That Kill: The Future Of Information Warfare – CB Insights report.