Freemium Pricing Model

The Freemium Pricing Model is getting increasingly incumbent in the gaming, web and software industries, and penetrating into education (online courses) and other industries too, as customers are becoming more accustomed to it. It’s not always the right model for every business, and even if it is, it may be tricky to find the right balance to ensure future profitability. There are many good and bad case studies to learn from. Andrew Chan also provides a free Excel spreadsheet to help you calculate the viability of the model in your business.

Attracting users and customers to a new start-up isn’t an easy task. Using the bell diagram of consumer adoption, we know that we first have to go for the risk takers, the early adopters, the weird and the wonderful, to take our product for a test run, give it a try, and give us some feedback (directly or indirectly) as they go.

One of a the more popular pricing models which many software, gaming or web services companies use, is The Freemium model.

However, nothing is completely free. Providing your product or service may be free to the consumer, but it will still cost you to deliver. A US based social media service, SumAll, have provided their services for free to over half a million subscribers. The cost of providing this free service was over US$4,000,000 last year!!

Even if your start-up is well funded, this isn’t an attractive proposition for your backers and investors. In the “pre-historic” days of the internet, PayPal ultimately paid $20 for people to use their service. Not only a free service – but a service that paid their first customers to use it, and evangelise it at the same time. It turns out to be the lowest form of Customer Acquisition Cost [CAC]. As Peter Thiel (one of PayPal’s founders) described it:

“PayPal’s big challenge was to get new customers. They tried advertising. It was too expensive. They tried BD deals with big banks. Bureaucratic hilarity ensued. Over ice cream, the PayPal team reached an important conclusion: BD didn’t work. They needed organic, viral growth. They needed to give people money.

So that’s what they did. New customers got $10 for signing up, and existing ones got $10 for referrals. Growth went exponential, and PayPal wound up paying $20 for each new customer. It felt like things were working and not working at the same time; 7 to 10% daily growth and 100 million users was good. No revenues and an exponentially growing cost structure were not. Things felt a little unstable. PayPal needed buzz so it could raise more capital and continue on. (Ultimately, this worked out. That does not mean it’s the best way to run a company. Indeed, it probably isn’t.)”

Not many companies can afford similar tactics, and today we have many tools in our marketing arsenal, which are a lot cheaper (or free!) to use, and gain real traction, without resorting to paying people to use our product.

In the past couple of days, I’ve received two emails from services I’ve subscribed to, announcing the end of the Free service, and presenting an ultimatum – “pay us [at 50% of RRP or blah blah blah) now, or we’re taking away part of the services”. One of those services gave me 7 days, the other was more generous, allowing me 14 days to consider.

There’s just one problem with that approach: You remember I mentioned it is very difficult to attract first users / subscribers to try out new service? You should really embrace those early adopters (even though some have already gone and tried other things in that time), as they’ve had a massive role in growing your business / subscriber / user base.

On one hand, you have investors screaming at you that your business isn’t sustainable, and they refuse to cough out more money and subsidise your business anymore.

On the other hand, you have those early adopters, evangelistic user base that have been enjoying your service (admittedly – for free) for the past few months / years, and you certainly don’t want to lose them either!

You feel trapped between those two polarising powers, so what do you do?

There are a few ways to approach this situation:

- Panic! Investors are threatening to pull out, so you panic and cut out all free users, in a hope they’ll convert into paying customers. Those two emails I’ve received from SumAll and li are examples of such behaviour. Or, ici

- Tweak. Try and limit usage of certain features, to see if this helps conversion of free to paid customers. Take New York Times website for example. After years of unrestricted access, in 2011 the paper began limiting users to 20 free articles a month; people had to subscribe if they wanted to read more. Over subsequent months the company realized it was still giving away too much and was getting too few subscribers as a result, so in 2012 it cut the number of free monthly articles to 10.

- Innovate. Offer additional services or features to your user-base, which will make sense for them to purchase. The best example I can think of is the iOS game Real Racing 3. Real Racing 3 by Firemonkeys and EA is one of the best racing games out there for iOS. The fact it comes as a free download with in-app purchases frustrates some – myself included – but it has at least opened up the opportunity to play to many, many more. The in-app purchases keep on coming, and as a player, you have the choice of earning many of the features (just by playing more), or you can make shortcuts, and pay to get those features and upgrades. Or,

Try and avoid getting into that situation in the first place! The first question you should ask yourself:

Is Freemium the right business model for me?

A business is setup to ultimately drive profitability. Choosing a Freemium model, we need to make sure we can eventually make money from it. To become profitable using a freemium business model, this simple equation must hold true:

Lifetime value > Cost per acquisition + Cost of service (paying & free)

In other words, the lifetime value of your paying customers needs to be greater than the cost it took to acquire them, plus, the cost servicing all users (free or paying).

There are lots of different factors that influence profitability, including:

- Cost per acquisition

- Efficiency of media (traffic sources, CTR, impressions)

- Signup funnel conversion %

- Average viral invites sent out

- Lifetime value

- Retention metrics

- Revenue mix

By understanding these sub-components, you can tweak your model and figure out what metrics need to be hit in order to reach profitability. Find more details on Andrew Chan’s blog.

If you can’t tweak the model to make it profitable, or you find other means of attracting the right customers who will pay upfront – the Freemium Model is not for you.

How are others using it?

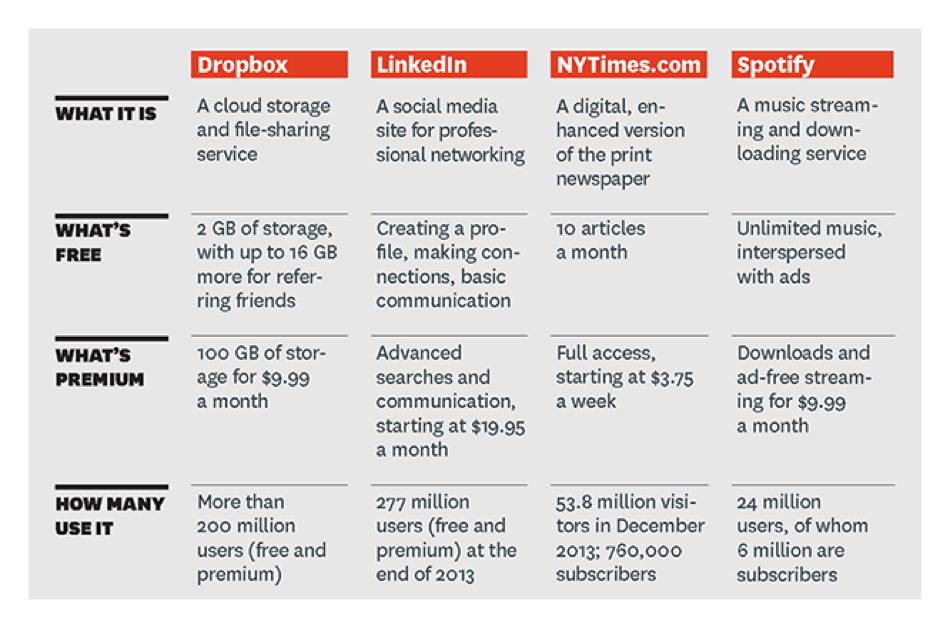

The Freemium model isn’t new, and many companies in the past 15+ years have used it to varying degrees of success. Among the biggest decisions facing “freemium” businesses are which features to make free and how much to charge for the rest. Research those you are aware of, starting with the 4 examples below.

Are my users evangelising my products?

It’s important to recognize the full value of your free users, which takes two forms: Some of them become subscribers, and some draw in new members who become subscribers (Evangelists). Harvard Business Review’s research found that free subscribers are typically worth 15%-25% of paid subscribers. If you’re considering a freemium model, pay close attention to why and how satisfied users might help your product go viral.

Are you committed to ongoing innovation?

It’s a mistake to see freemium merely as a customer acquisition tool and to drop the free version when new customers stop coming in or when the upgrade rate dives. Users who join late are typically harder to convert; therefore, in order to keep increasing upgrades, you’ll need to keep increasing the value of your premium services. Smart companies view freemium not only as a revenue model but also as a commitment to innovation.

Real Racing 3 is a great example – the updates are coming often, with more cars, more races, and more modification features for the cars.

Is my offering clear?

Looking at the many features of any online / mobile services, it’s not always easy to determine where the free offer stops, and the “mium” offer begins. Looking at LinkedIn for example, the average user can’t easily tell which of the features are free, and what are the benefits of become a premium subscriber. Most LinkedIn users will know about the vertical offering to sales people, recruiters and advertising platform. However, not many will know how many search results or number of InMails are available with each package.

In contrast, Dropbox offers 2GB free for all users, forever. That’s enough for many users for storing documents. However, if you need more space (to store media files), you can get 100GB for $9.99 per month. Clear and simple.

Of course, Dropbox offers business packages as well, including collaboration tools etc. too, however it’s not part of the freemium model, but a separate business offering altogether.

Take your time to evaluate your own situation, and decide what’s right for you. If in doubt, just ask for help!

[ssm_form id=’3277′]

This is very true in a consumer context, but an enterprise context has a slightly different dynamic. Not only can you segment customers across the adoption spectrum, but within each customer there are also people who define “value” differently.

In a consumer context, an adopter typically starts by becoming a user of the free version. Potential purchasers then need to find a compelling reason to pay for premium, as against keeping their free subscription. The adopter, user, and potential purchaser are all the same person.

In contrast, the enterprise context allows the adopter (individual) to find no additional value in the premium version, and the potential purchaser (again, an individual) to find no value in the free version.

To use quite a basic example, people in your company might want to gather feedback using a survey tool. For the person actually collecting data, the data won’t be any better if they use premium version, so the free version is fine. To someone managing your corporate brand, it may be worth paying for the premium service to customize the logo and color scheme of the surveys. In this case, the actual purchaser of a survey tool might not even collect any data themselves!

Some services have done this well, others have failed even with very similar business models. The subtle differences seem to be deciding what the premium features are, making sure they are relevant to the target purchasing audience, and timing the sales conversation to incorporate the voice of those early adopters.

Thanks for your comment Ben. Many tech startups will have a consumer freemium model, where it’s free to a certain level of usage for individuals, and has a premium enterprise service. Yammer is an obvious example, but there are many others – Dropbox, Linkedin, MailChimp, Hootsuite, and others.

I completely agree with you, that it’s the decision about which features should be premium, based on the target audience (free & purchasing), that can determine the success or failure of such model.